# Types of path-specific causal mediation effects {#estimands}

```{r}

#| label: load-renv

#| echo: false

#| message: false

renv::autoload()

library(here)

```

- Controlled direct effects

- Natural direct and indirect effects

- Randomized interventional direct and indirect effects

- Path-specific effects using *recanting twins*

```{tikz}

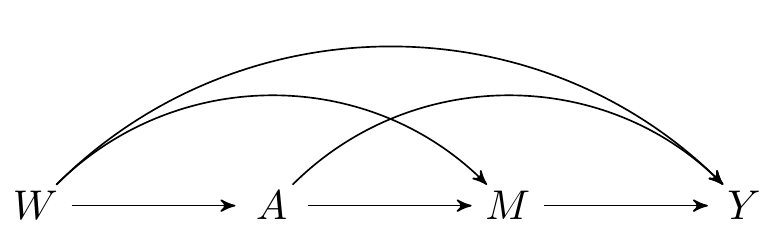

#| fig-cap: Directed acyclic graph under *no intermediate confounders* of the mediator-outcome relation affected by treatment

\dimendef\prevdepth=0

\pgfdeclarelayer{background}

\pgfsetlayers{background,main}

\usetikzlibrary{arrows,positioning}

\tikzset{

>=stealth',

punkt/.style={

rectangle,

rounded corners,

draw=black, very thick,

text width=6.5em,

minimum height=2em,

text centered},

pil/.style={

->,

thick,

shorten <=2pt,

shorten >=2pt,}

}

\newcommand{\Vertex}[2]

{\node[minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\VertexR}[2]

{\node[rectangle, draw, minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\ArrowR}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend right=30] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\ArrowL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend left=45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\EdgeL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[dashed,#3] (#1) to[bend right=-45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\Arrow}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) -- +(#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\Vertex{-4, 0}{W}

\Vertex{0, 0}{M}

\Vertex{-2, 0}{A}

\Vertex{2, 0}{Y}

\Arrow{W}{A}{black}

\Arrow{A}{M}{black}

\Arrow{M}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{W}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{A}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{W}{M}{black}

\end{tikzpicture}

```

## Controlled direct effects

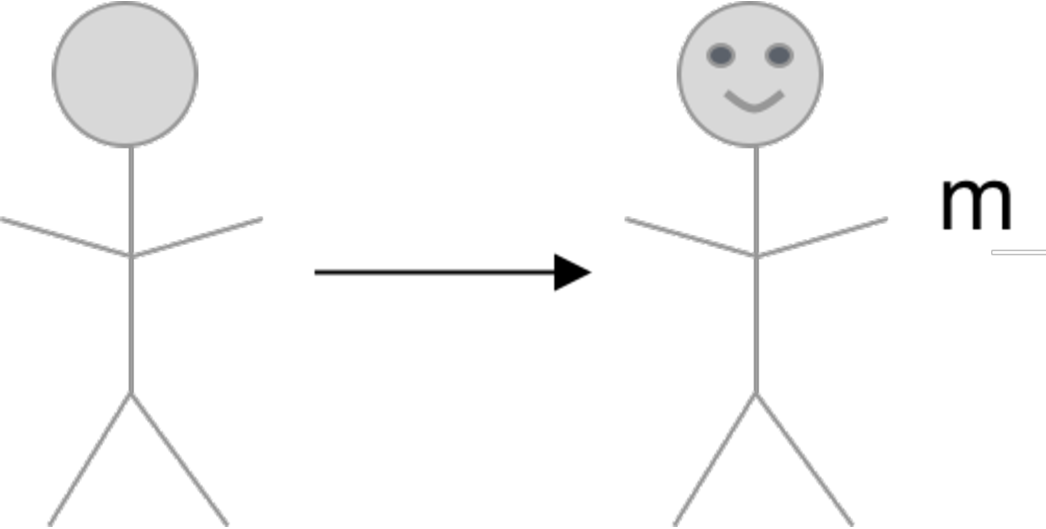

$$\psi_{\text{CDE}} = \E(Y_{1,m} - Y_{0,m})$$

{width="40%"}

- Intervening on the SCM to set $M=m$ uniformly for everyone in the population

- Compare $A=1$ vs $A=0$ with $M=m$ fixed

### Identification assumptions:

- Confounder assumptions:

- $A \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W$

- $M \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W, A$

- Positivity assumptions:

- $\P(M = m \mid A=a, W) > 0 \text{ } a.e.$

- $\P(A=a \mid W) > 0 \text{ } a.e.$

Under the above identification assumptions, the controlled direct effect can be identified: $$

\E(Y_{1,m} - Y_{0,m}) = \E\{ \color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M=m, W) -

\E(Y \mid A=0, M=m, W)} \}

$$

- For intuition about this formula in R, let's continue with a toy example:

```{webr-r}

n <- 1e6

w <- rnorm(n)

a <- rbinom(n, 1, 0.5)

m <- rnorm(n, w + a)

y <- rnorm(n, w + a + m)

```

- First we fit a correct model for the outcome

```{webr-r}

lm_y <- lm(y ~ m + a + w)

```

- Assume we would like the CDE at $m=0$

- Then we generate predictions $$

\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M=m, W)}

\text{ and } \color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=0, M=m, W)} \ :

$$

```{webr-r}

pred_y1 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(a = 1, m = 0, w = w))

pred_y0 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(a = 0, m = 0, w = w))

```

- Then we compute the difference between the predicted values $\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M=m, W) - \E(Y \mid A=0, M=m, W)}$, and average across values of $W$

```{webr-r}

## CDE at m = 0

mean(pred_y1 - pred_y0)

```

### Is this the estimand I want?

- Makes the most sense if it is reasonable for everyone have a constant level $m

\in \mathcal{M}$.

- Judea Pearl calls this *prescriptive*.

- Can you think of an example? (Air pollution, rescue inhaler dosage, hospital visits...)

- Does not provide a decomposition of the average treatment effect into direct and indirect effects.

*What if everyone having the same value of the mediator doesn't make sense?*

*What if we want to decompose the average treatment effect into its direct and indirect counterparts?*

## Natural direct and indirect effects

Continuing to use the same DAG as above,

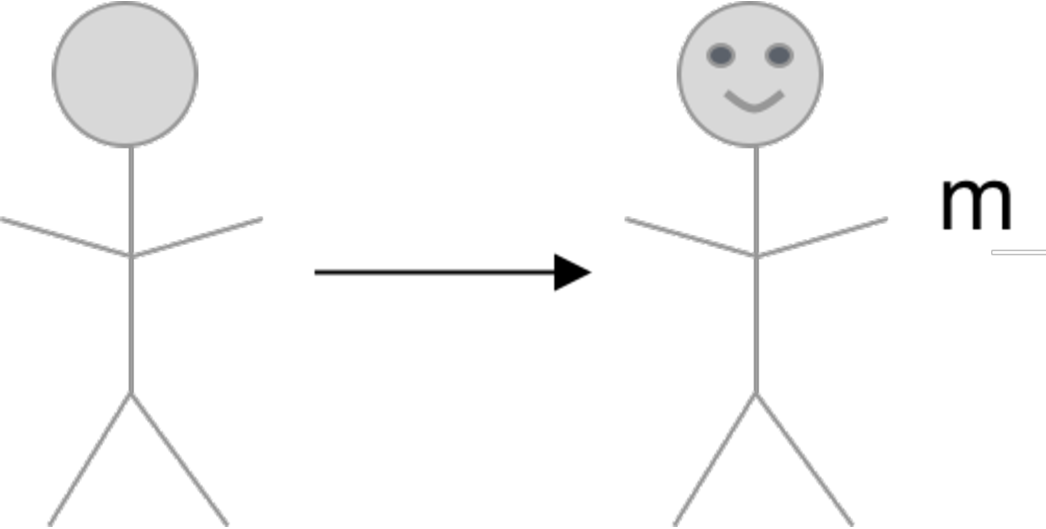

- Recall the definition of the nested counterfactual: \begin{equation*}

Y_{1, M_0} = f_Y(W, 1, M_0, U_Y)

\end{equation*}

- Interpreted as *the outcome for an individual in a hypothetical world where treatment was given but the mediator was held at the value it would have taken under no treatment*

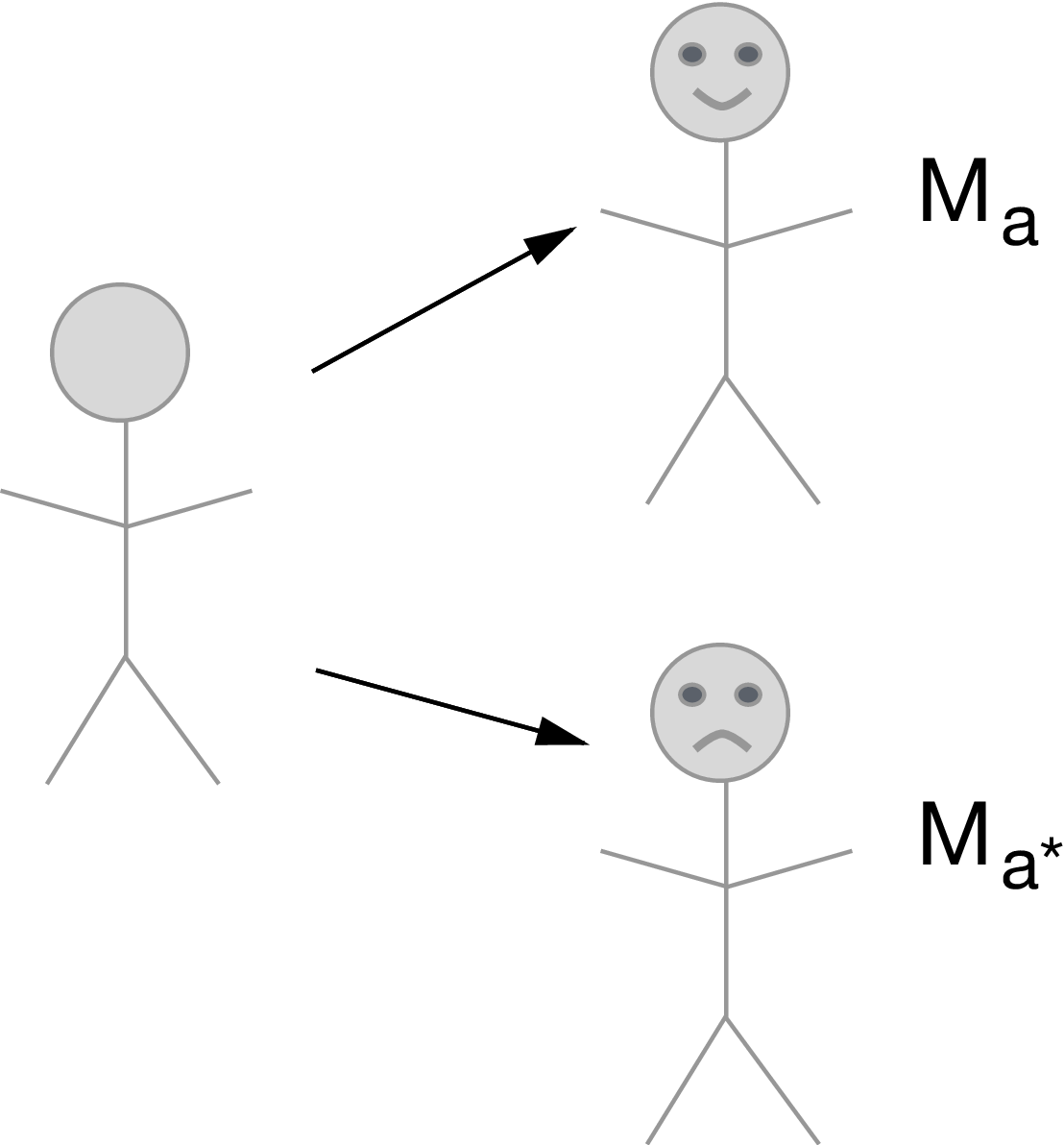

{width="40%"}

- Recall that, because of the definition of counterfactuals \begin{equation*}

Y_{1, M_1} = Y_1

\end{equation*}

Then we can decompose the *average treatment effect* $\E(Y_1-Y_0)$ as follows

\begin{equation*}

\E[Y_{1,M_1} - Y_{0,M_0}] = \underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{red}{1},\color{blue}{M_1}}

- Y_{\color{red}{1},\color{blue}{M_0}}]}_{\text{natural indirect effect}} +

\underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{blue}{1},\color{red}{M_0}} -

Y_{\color{blue}{0},\color{red}{M_0}}]}_{\text{natural direct effect}}

\end{equation*}

- Natural direct effect (NDE): Varying treatment while keeping the mediator fixed at the value it would have taken under no treatment

- Natural indirect effect (NIE): Varying the mediator from the value it would have taken under treatment to the value it would have taken under control, while keeping treatment fixed

### Identification assumptions:

- $A \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W$

- $M \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W, A$

- $A \indep M_a \mid W$

- $M_0 \indep Y_{1,m} \mid W$

- and positivity assumptions

### Cross-world independence assumption

What does $M_0 \indep Y_{1,m} \mid W$ mean?

- Conditional on $W$, knowledge of the mediator value in the absence of treatment, $M_0$, provides no information about the outcome under treatment, $Y_{1,m}$.

- Can you think of a data-generating mechanism that would violate this assumption?

- Example: in a randomized study, whenever we believe that treatment assignment works through adherence (i.e., almost always), we are violating this assumption (more on this later).

- Cross-world assumptions are problematic for other reasons, including:

- You can never design a randomized study where the assumption holds by design.

**If the cross-world assumption holds, can write the NDE as a weighted average of controlled direct effects at each level of** $M=m$.

$$

\E \sum_m \{\E(Y_{1,m} \mid W) - \E(Y_{0,m} \mid W)\} \P(M_{0}=m \mid W)

$$

- If CDE($m$) is constant across $m$, then CDE = NDE.

### Identification formula:

- Under the above identification assumptions, the natural direct effect can be identified: \begin{equation*}

\E(Y_{1,M_0} - Y_{0,M_0}) =

\E[\color{red}{\E\{}\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M, W) -

\E(Y \mid A=0, M, W)}\color{red}{\mid A=0,W\}}]

\end{equation*}

- The natural indirect effect can be identified similarly.

- Let's dissect this formula in `R`:

```{webr-r}

n <- 1e6

w <- rnorm(n)

a <- rbinom(n, 1, 0.5)

m <- rnorm(n, w + a)

y <- rnorm(n, w + a + m)

```

- First we fit a correct model for the outcome

```{webr-r}

lm_y <- lm(y ~ m + a + w)

```

- Then we generate predictions $\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M, W)}

\text{ and }\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=0, M, W)}$ with $A$ fixed but letting $M$ and $W$ take their observed values

```{webr-r}

pred_y1 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(a = 1, m = m, w = w))

pred_y0 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(a = 0, m = m, w = w))

```

- Then we compute the difference between the predicted values $\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M, W) - \E(Y \mid A=0, M, W)},$

- and use this difference as a pseudo-outcome in a regression on $A$ and $W$: $\color{red}{\E\{}\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=1, M, W) -

\E(Y \mid A=0, M, W)}\color{red}{\mid A=0,W\}}$

```{webr-r}

pseudo <- pred_y1 - pred_y0

lm_pseudo <- lm(pseudo ~ a + w)

```

- Now we predict the value of this pseudo-outcome under $A=0$, and average the result

```{webr-r}

pred_pseudo <- predict(lm_pseudo, newdata = data.frame(a = 0, w = w))

## NDE:

mean(pred_pseudo)

```

### Is this the estimand I want?

- Makes sense to hypothetically set $A$ but not $M$.

- Want to understand a natural mechanism underlying an association or total effect. Judea Pearl calls this *descriptive*.

- NDE + NIE = total effect (ATE).

- Okay with the assumptions.

*What if our data structure involves a post-treatment confounder of the mediator-outcome relationship (e.g., adherence)?*

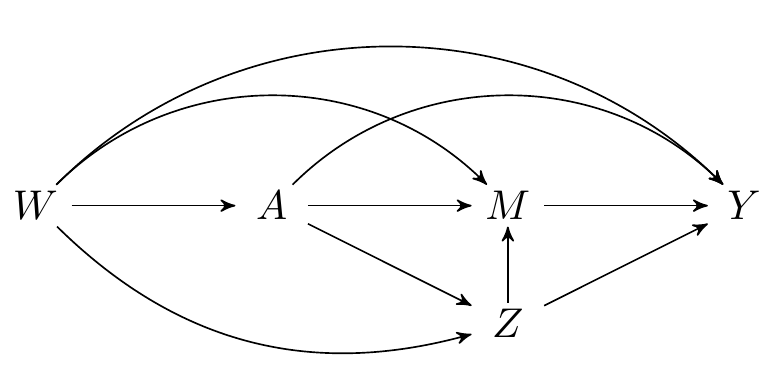

```{tikz}

#| fig-cap: Directed acyclic graph under intermediate confounders of the mediator-outcome relation affected by treatment

\dimendef\prevdepth=0

\pgfdeclarelayer{background}

\pgfsetlayers{background,main}

\usetikzlibrary{arrows,positioning}

\tikzset{

>=stealth',

punkt/.style={

rectangle,

rounded corners,

draw=black, very thick,

text width=6.5em,

minimum height=2em,

text centered},

pil/.style={

->,

thick,

shorten <=2pt,

shorten >=2pt,}

}

\newcommand{\Vertex}[2]

{\node[minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\VertexR}[2]

{\node[rectangle, draw, minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\ArrowR}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend right=30] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\ArrowL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend left=45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\EdgeL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[dashed,#3] (#1) to[bend right=-45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\Arrow}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) -- +(#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\Vertex{0, -1}{Z}

\Vertex{-4, 0}{W}

\Vertex{0, 0}{M}

\Vertex{-2, 0}{A}

\Vertex{2, 0}{Y}

\ArrowR{W}{Z}{black}

\Arrow{Z}{M}{black}

\Arrow{W}{A}{black}

\Arrow{A}{M}{black}

\Arrow{M}{Y}{black}

\Arrow{A}{Z}{black}

\Arrow{Z}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{W}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{A}{Y}{black}

\ArrowL{W}{M}{black}

\end{tikzpicture}

```

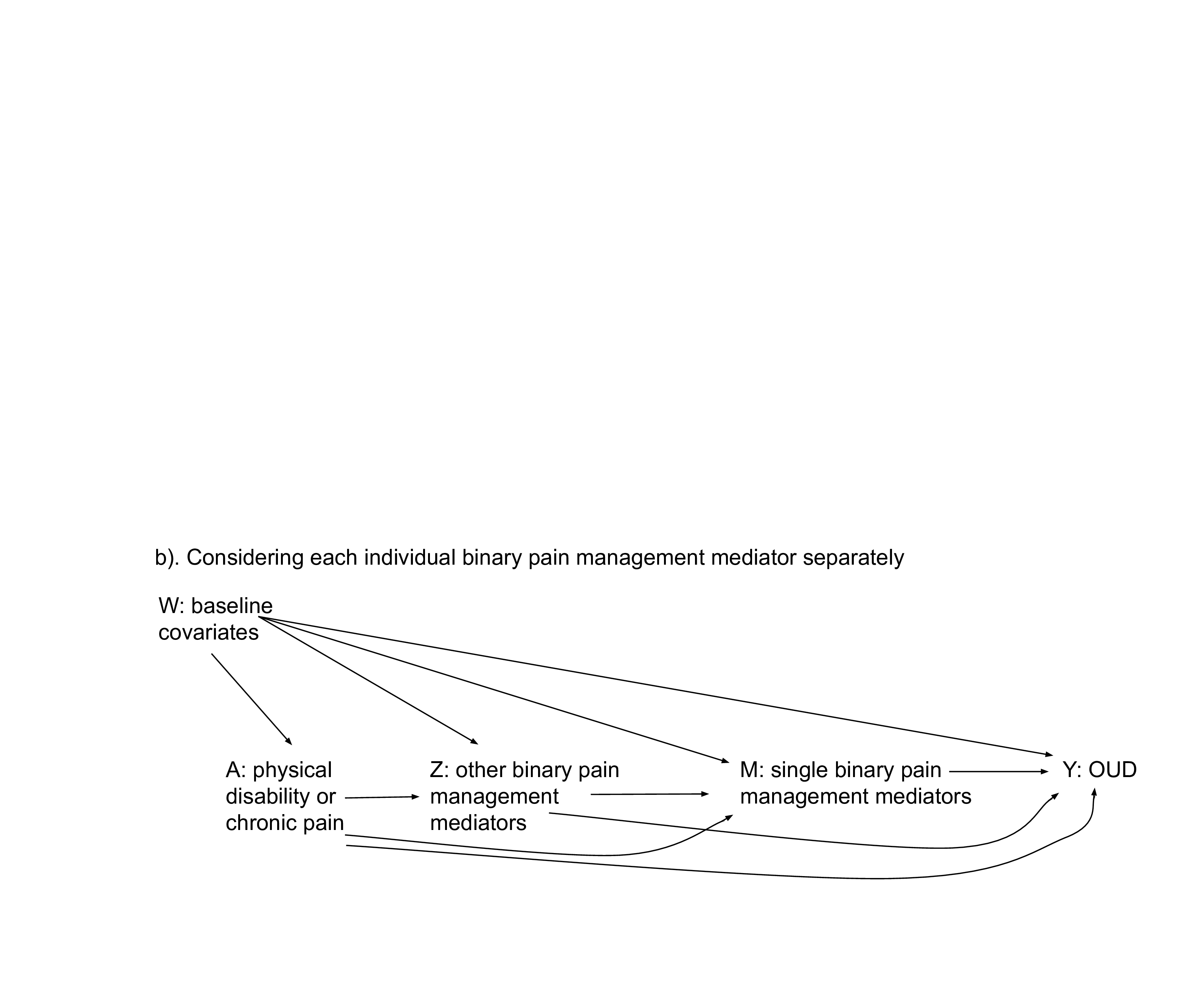

{width="80%"}

### Unidentifiability of the NDE and NIE in this setting

- In this example, natural direct and indirect effects are not generally point identified from observed data $O=(W,A,Z,M,Y)$.

- The reason for this is that the cross-world counterfactual assumption $$Y_{1,m} \indep M_0 \mid W$$ does not hold in the above directed acyclic graph.

- To give intuition, we focus on the counterfactual outcome $Y_{A=1, M_{A=0}}$.

- This counterfactual outcome involves two counterfactual worlds simultaneously: one in which $A=1$ for the first portion of the counterfactual outcome, and one in which $A=0$ for the nested portion of the counterfactual outcome.

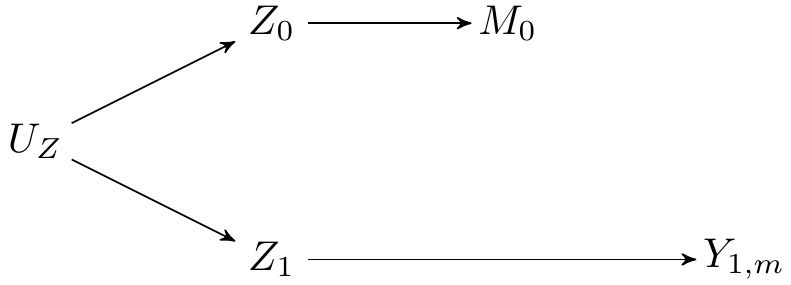

- Setting $A=1$ induces a counterfactual treatment-induced confounder, denoted $Z_{A=1}$. Setting $A=0$ induces another counterfactual treatment-induced confounder, denoted $Z_{A=0}$.

- The two treatment-induced counterfactual confounders, $Z_{A=1}$ and $Z_{A=0}$ share unmeasured common causes, $U_Z$, which creates a spurious association.

- Because $Z_{A=1}$ is causally related to $Y_{A=1, M=m}$, and $Z_{A=0}$ is also casually related to $M_{A=0}$, the path through $U_Z$ means that the backdoor criterion is not met for identification of $Y_{A=1, M_{A=0}}$, i.e., $M_{0} \notindep Y_{A=1, m} \mid W$, where $W$ denotes baseline covariates.

```{tikz}

#| fig-cap: Parallel worlds model of the scenario considered

\dimendef\prevdepth=0

\pgfdeclarelayer{background}

\pgfsetlayers{background,main}

\usetikzlibrary{arrows,positioning}

\tikzset{

>=stealth',

punkt/.style={

rectangle,

rounded corners,

draw=black, very thick,

text width=6.5em,

minimum height=2em,

text centered},

pil/.style={

->,

thick,

shorten <=2pt,

shorten >=2pt,}

}

\newcommand{\Vertex}[2]

{\node[minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\VertexR}[2]

{\node[rectangle, draw, minimum width=0.6cm,inner sep=0.05cm] (#2) at (#1) {$#2$};

}

\newcommand{\ArrowR}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend right=30] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\ArrowL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) to[bend left=45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\EdgeL}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[dashed,#3] (#1) to[bend left=45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\EdgeR}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[dashed,#3] (#1) to[bend right=-45] (#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\newcommand{\Arrow}[3]

{ \begin{pgfonlayer}{background}

\draw[->,#3] (#1) -- +(#2);

\end{pgfonlayer}

}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\Vertex{0, 1}{Z_0}

\Vertex{0, -1}{Z_1}

\Vertex{-2, 0}{U_Z}

\Vertex{2, 1}{M_0}

\Vertex{4, -1}{Y_{1, m}}

\Arrow{Z_0}{M_0}{black}

\Arrow{Z_1}{Y_{1, m}}{black}

\Arrow{U_Z}{Z_0}{black}

\Arrow{U_Z}{Z_1}{black}

\end{tikzpicture}

```

```{=html}

<!--

this is what we used to have

- Technically, the reason for this is that an intervention setting $A=1$

(necessary for the definition of $Y_{1,m}$) induces a counterfactual variable

$Z_1$.

- Likewise, an intervention setting $A=0$ (necessary for the definition of

$M_0$) induces a counterfactual $Z_0$.

- The variables $Z_1$ and $Z_0$ are correlated because they share unmeasured

common causes, $U_Z$.

- The variable $Z_1$ is correlated with $Y_{1,m}$, and the variable $Z_0$ is

correlated with $M_0$, because they are counterfactual outcomes in the same

hypothetical worlds.

- To see this in the definition of counterfactual from a causal structural

model:

\begin{align*}

Y_{1,m} &= f_Y(W, 1, Z_1, m, U_Y), \text{ and }\\

M_0 &= f_M(W, 0, Z_0, U_M)\\

\end{align*}

are correlated even after adjusting for $W$ by virtue of $Z_1$ and $Z_0$ being

correlated.

-->

```

```{=html}

<!--

Intuitively:

- $Z$ is a confounder of the relation $M \rightarrow Y$, which requires

adjustment

- But $Z$ is on the pathway $A\rightarrow Y$, which precludes adjustment

-->

```

However:

- We can actually identify the NIE/NDE if we are willing to invoke monotonicity between a treatment and one or more binary treatment-induced confounders [@tchetgen2014identification].

- Assuming monotonicity is also sometimes referred to as assuming "no defiers"---in other words, assuming that there are no individuals who would do the opposite of the encouragement.

- Monotonicity may seem like a restrictive assumption, but may be reasonable in some common scenarios (e.g., in trials where the intervention is randomized treatment assignment and the treatment-induced confounder is whether or not treatment was actually taken---in this setting, we may feel comfortable assuming that there are no "defiers", frequently assumed when using IVs to identify causal effects)

Note: CDEs are still identified in this setting. They can be identified and estimated similarly to a longitudinal data structure with a two-time-point intervention.

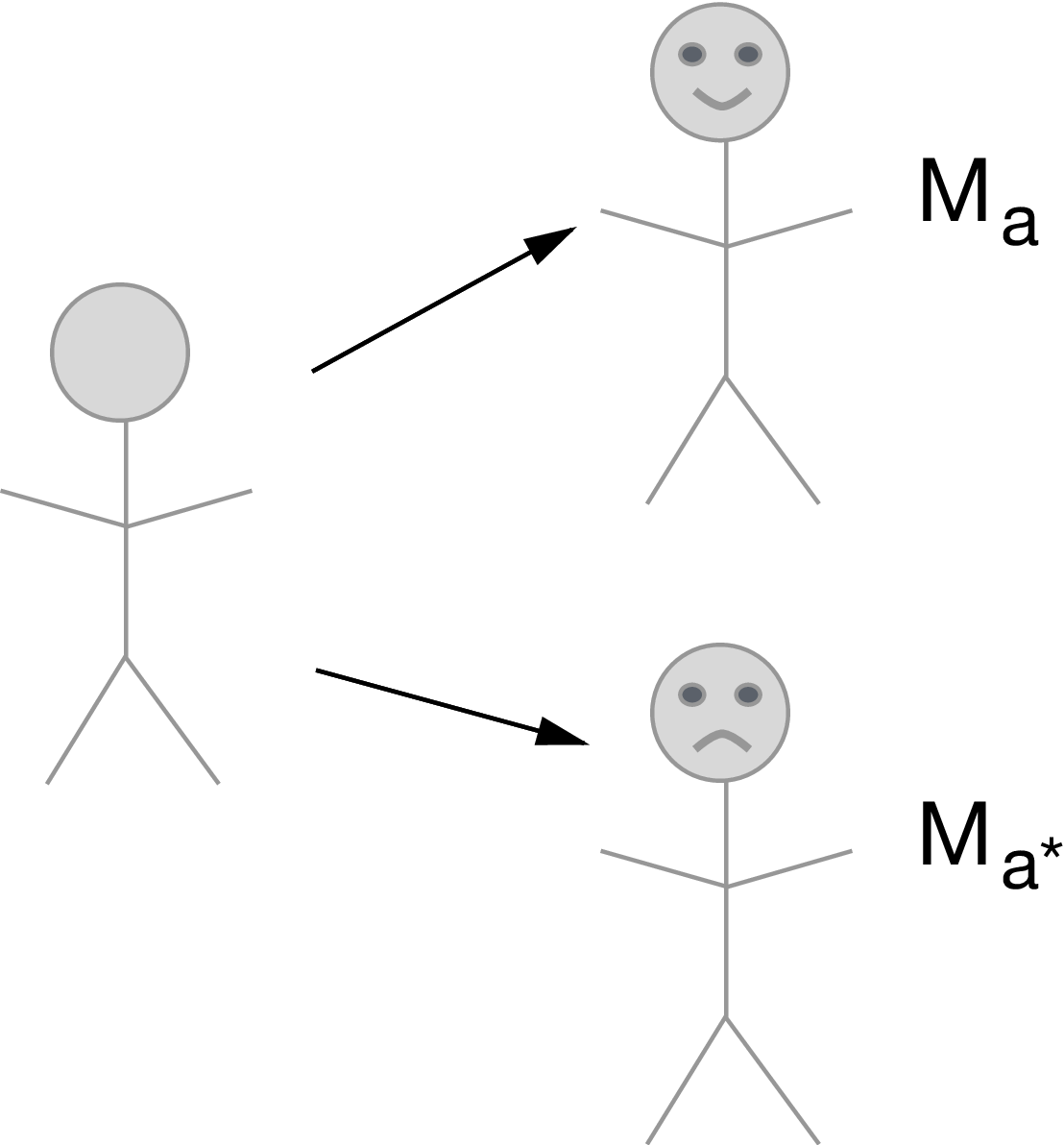

## Randomized interventional (in)direct effects

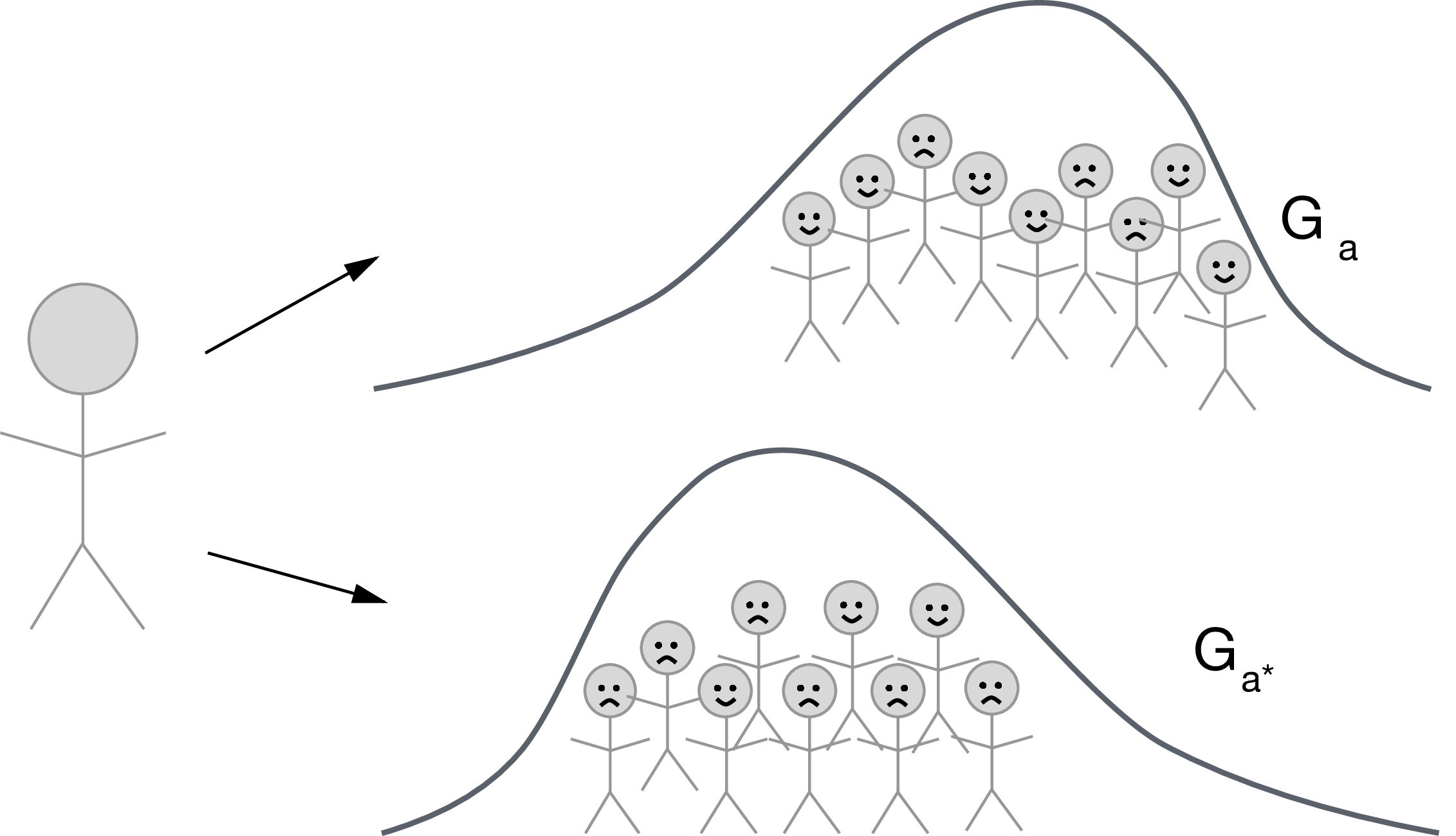

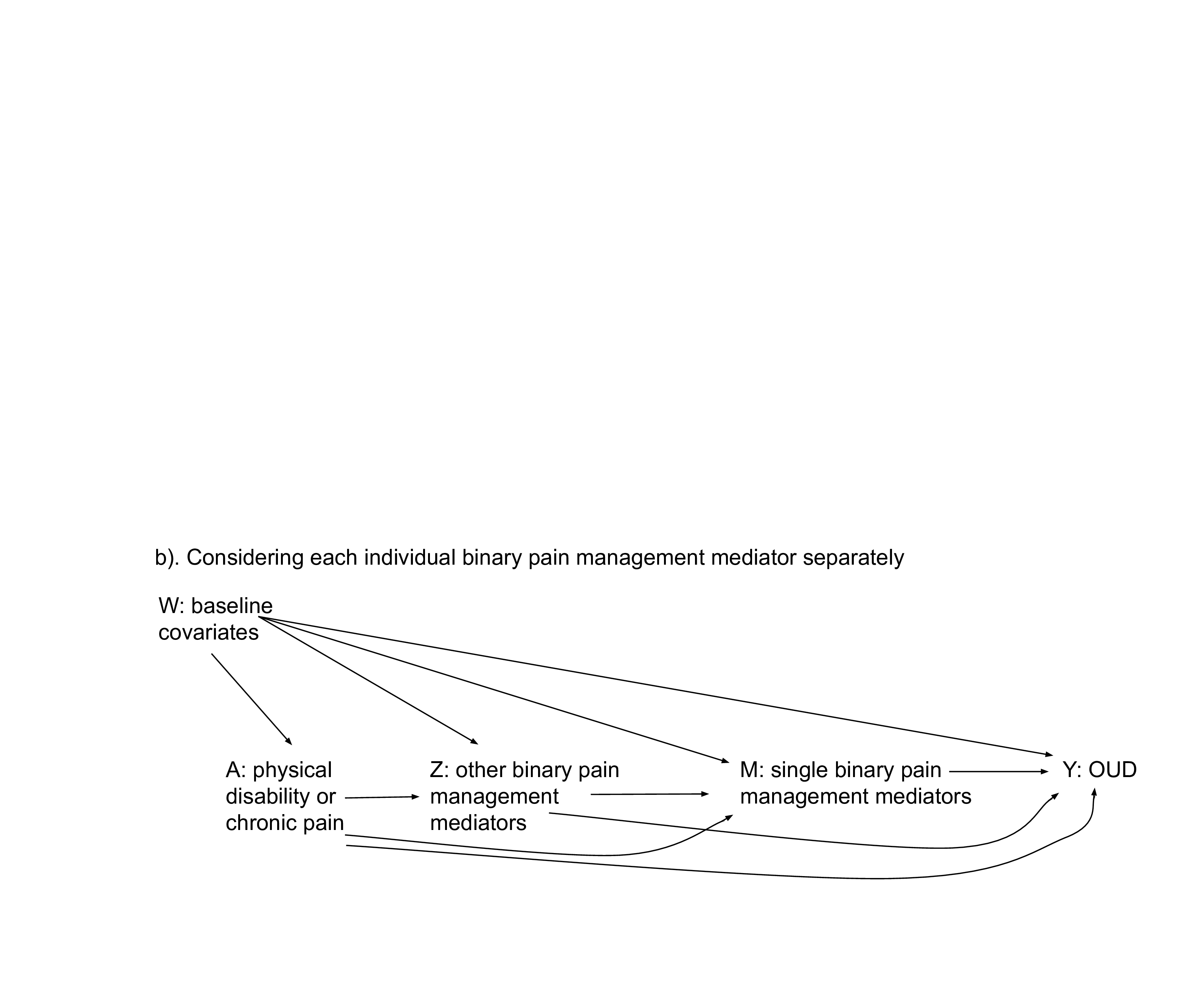

- Let $G_a$ denote a random draw from the distribution of $M_a \mid W$

- Define the counterfactual $Y_{1,G_0}$ as the counterfactual variable in a hypothetical world where $A$ is set $A=1$ and $M$ is set to $M=G_0$ with probability one.

{width="60%"}

- Define $Y_{0,G_0}$ and $Y_{1,G_1}$ similarly

- Then we can define: $$

\E[Y_{1,G_1} - Y_{0,G_0}] = \underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{red}{1},

\color{blue}{G_1}} - Y_{\color{red}{1},

\color{blue}{G_0}}]}_{\text{interventional indirect effect}} +

\underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{blue}{1},\color{red}{G_0}} -

Y_{\color{blue}{0},

\color{red}{G_0}}]}_{\text{interventional direct effect}}

$$

- Note that $\E[Y_{1,G_1} - Y_{0,G_0}]$ is still an *overall effect* of treatment, even if it is different from the ATE $\E[Y_{1} - Y_{0}]$

- We gain in the ability to solve a problem, but lose in terms of interpretation of the causal effect (cannot decompose the ATE)

### An alternative definition of the effects:

- Above we defined $G_a$ as a random draw from the distribution of $M_a \mid W$

- What if instead we define $G_a$ as a random draw from the distribution of $M_a \mid (Z_a,W)$

- It turns out the indirect effect defined in this way only measures the path $A \rightarrow M \rightarrow Y$, and not the path $A \rightarrow Z \rightarrow M \rightarrow Y$

- There may be important reasons to choose one over another (e.g., survival analyses where we want the distribution conditional on $Z$, instrumental variable designs where it doesn't make sense to condition on $Z$)

```{=html}

<!--

+ Marginal PIDE: $\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid a^{\star}, W}}) -

\E(Y_{a^{\star}, g_{M \mid a^{\star}, W}})$

+ Marginal PIIE: $\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid a, W}}) -

\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid a^{\star}, W}})$

+ Conditional PIDE: $\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid Z, a^{\star}, W}}) -

\E(Y_{a^{\star}, g_{M \mid Z, a^{\star}, W}})$

+ Conditional PIIE: $\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid Z, a, W}}) -

\E(Y_{a, g_{M \mid Z, a^{\star}, W}})$

+ Can you think of an example when you would want the conditional versions?

Marginal versions?

-->

```

### Identification assumptions:

- $A \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W$

- $M \indep Y_{a,m} \mid W, A, Z$

- $A \indep M_a \mid W$

- and positivity assumptions.

Under these assumptions, the randomized interventional direct and indirect effect is identified: \begin{align*}

\E &(Y_{a, G_{a'}}) = \\

& \E\left[\color{Purple}{\E\left\{\color{red}{\sum_z}

\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=a, Z=z, M, W)}

\color{red}{\P(Z=z \mid A=a, W)}\mid A=a', W\right\}} \right]

\end{align*}

- Let's dissect this formula in `R`:

```{webr-r}

n <- 1e6

w <- rnorm(n)

a <- rbinom(n, 1, 0.5)

z <- rbinom(n, 1, 0.5 + 0.2 * a)

m <- rnorm(n, w + a - z)

y <- rnorm(n, w + a + z + m)

```

- Let us compute $\E(Y_{1, G_0})$ (so that $a = 1$, and $a'=0$).

- First, fit a regression model for the outcome, and compute $\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=a, Z=z, M, W)}$ for all values of $z$

```{webr-r}

lm_y <- lm(y ~ m + a + z + w)

pred_a1z0 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(m = m, a = 1, z = 0, w = w))

pred_a1z1 <- predict(lm_y, newdata = data.frame(m = m, a = 1, z = 1, w = w))

```

- Now we fit the true model for $Z \mid A, W$ and get the conditional probability that $Z=1$ fixing $A=1$

```{webr-r}

prob_z <- lm(z ~ a)

pred_z <- predict(prob_z, newdata = data.frame(a = 1))

```

- Now we compute the following pseudo-outcome: $\color{red}{\sum_z}\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=a, Z=z, M, W)}

\color{red}{\P(Z=z \mid A=a, w)}$

```{webr-r}

pseudo_out <- pred_a1z0 * (1 - pred_z) + pred_a1z1 * pred_z

```

- Now we regress this pseudo-outcome on $A,W$, and compute the predictions setting $A=0$, that is, $$

\color{Purple}{\E\left\{\color{red}{\sum_z}

\color{ForestGreen}{\E(Y \mid A=a, Z=z, M, W)}

\color{red}{\P(Z=z \mid A=a, w)}\mid A=a', W\right\}}

$$

```{webr-r}

fit_pseudo <- lm(pseudo_out ~ a + w)

pred_pseudo <- predict(fit_pseudo, data.frame(a = 0, w = w))

```

- And finally, just average those predictions!

```{webr-r}

# Mean(Y(1, G(0)))

mean(pred_pseudo)

```

- This was for $(a,a')=(1,0)$. Can do the same with $(a,a')=(1,1)$, and $(a,a')=(0,0)$ to obtain an effect decomposition

\begin{equation*}

\E[Y_{1,G_1} - Y_{0,G_0}] = \underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{red}{1},

\color{blue}{G_1}} -

Y_{\color{red}{1},

\color{blue}{G_0}}]}_{\text{interventional indirect effect}} +

\underbrace{\E[Y_{\color{blue}{1},\color{red}{G_0}} -

Y_{\color{blue}{0},

\color{red}{G_0}}]}_{\text{interventional direct effect}}

\end{equation*}

### Is this the estimand I want?

- Do not want to intervene directly on $M$ in the causal model.

- Goal is to understand a descriptive type of mediation.

- Okay with the assumptions!

### But, there is an important limitation of randomized interventional effects

@miles2022causal recently uncovered an important limitation of these effects, which can be described as follows. The sharp mediational null hypothesis can be defined as

$$

H_0:Y(a, M(a')) = Y(a, M(a^\star));\text{ for all }a, a', a^\star \ .

$$

The problem is that randomized interventional effects are not guaranteed to be null when the sharp mediational hypothesis is true.

This could present a problem in practice if some subgroup of the population has a relationship between $A$ and $M$, but not between $M$ and $Y$. Then, another distinct subgroup of the population has a relationship between $M$ and $Y$ but not between $A$ and $M$. In such a scenario, the randomized interventional indirect effect would be nonzero, but there would be no one person in the population whose effect of $A$ on $Y$ would be mediated by $M$.

```{=html}

<!--

One counterexample involves creating an NPSEM with independent errors,

$W=\emptyset$, and an exogenous binary variable $U_Z$ such that $M(a)

= M(a')$ in the event $U_Z=1$ and $Y(a,m') = Y(a,m)$ in the event

$U_Z=0$ for all $a$, $a'$, and $m$, such that there is no causal

influence of $A$ on $Y$ operating through $M$. It is easy to see that

the randomized interventional indirect effect in this example equals

\[\sum_{z,m} E(Y\mid m, z,a) P(Z=z\mid a)[P(M=m\mid a)-P(M=m\mid

a')],\]

which is generally not null, and would only be null if $U_Z$

was observed and conditioned upon in all the above quantities.

-->

```

More details can be found in the original paper.

## Path-specific effects using *recanting twins*

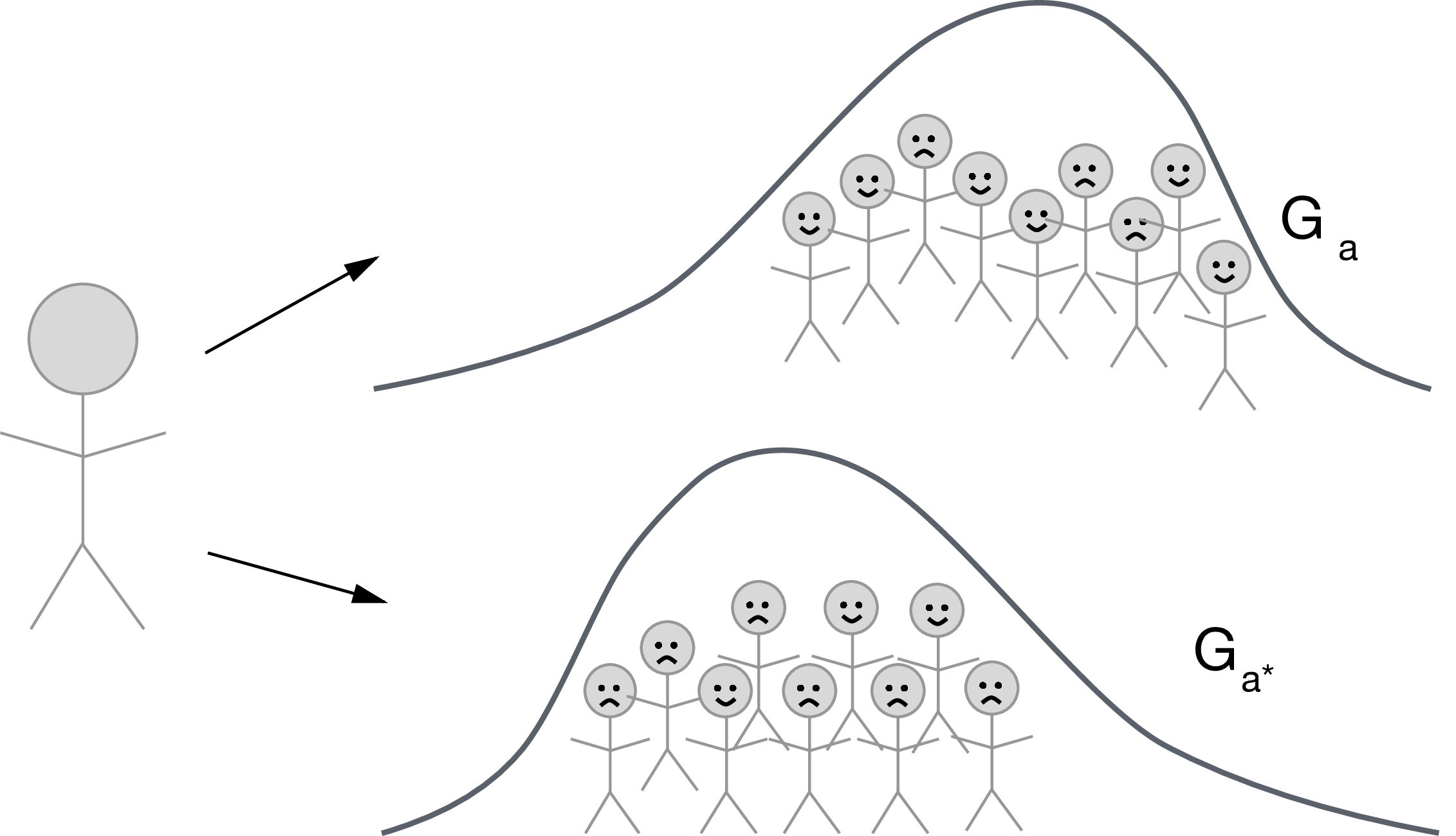

The DAG we are working under contains four paths of interest:

\begin{align*}

P_1&: A\rightarrow Y;\\

P_2&: A \rightarrow Z \rightarrow Y;\\

P_3&: A \rightarrow Z \rightarrow M \rightarrow Y\\

P_4&: A \rightarrow M \rightarrow Y,

\end{align*}

Natural path-specific effects could be defined using the following nested counterfactuals: \begin{align*}

Y_{S_0}&=Y(1, Z(1), M(1, Z(1))),\\

Y_{S_1}&=Y(0, Z(1), M(1, Z(1))),\\

Y_{S_2}&=Y(0, Z(0), M(1, Z(1))),\\

Y_{S_3}&=Y(0, Z(0), M(1, Z(0))),\\

Y_{S_4}&=Y(0, Z(0), M(0, Z(0))),

\end{align*}

As before, the problem is that the distribution of $Y_{S_2}$ is not identifiable due to the so-called recanting witness $Z$. This means that one can contrast $Y_{S_1}$ with $Y_{S_3}$ but not with $Y_{S_2}$. Thus, the effects operating through $P_2$ and $P_3$ cannot be disentangled.

$Z$ is called a recanting witness because "it tells one story" $Z(1)$ for the purposes of one path, and another story $Z(0)$ for the purposes of the other.

But what if we replaced recanting witnesses by randomized versions of them that carry some of the same information? Specifically, if $T(a)$ is a random draw from the distribution of $Z(a)$ conditional on $W$, we can:

- Measure $P_2$ by contrasting $$

Y(0, Z(1), M(1, {\color{ForestGreen}{T(1)}})) \text{ vs. }

Y(0, Z(0), M(1, \color{ForestGreen}{T(1)}))

$$

- Measure $P_3$ by contrasting $$

Y(0, {\color{ForestGreen}{T(0)}}, M(1, Z(1))) \text{ vs. }

Y(0, {\color{ForestGreen}{T(0)}}, M(1, Z(0)))

$$

- Measure the other paths through their identified natural effects

This is what we proposed in @vo2024recanting.

The variables $T(a)$ are the *recanting twins* of $Z(1-a)$. Identification requires some of the standard assumptions, namely:

- $U_A\indep (U_Y, U_M, U_Z)\mid W$,

- $U_Z\indep (U_Y, U_M)\mid (A,W)$, and

- $U_M\indep U_Y\mid (Z,A,W)$.

Under these assumptions, we can identify a decomposition of the ATE as follows:

$$

\text{ATE} = \psi_{P_1} + \psi_{P_2} + \psi_{P_3} + \psi_{P_4} +

\psi_{\text{IC}},

$$

where

- $\psi_{P_i}$ measures the effect through path $P_i$

- $\psi_{\text{IC}}$ is a remainder that is equal to zero if there is no intermediate confounding, in which case $\psi_{P_i}$ is equal to the (identified) natural path-specific effect.

More details on the definition, interpretation, and identification of these effects in the paper!